How to spot deepfake videos and AI audio

Did Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer yell profanities at his staff, or endorse an investment scheme? Did Mayor of London Sadiq Khan say that “Remembrance weekend” should be postponed in favour of a pro-Palestinian march? Almost certainly not, but realistic sounding video and audio clips recently spread online claiming that they did.

Even when there’s no evidence that such clips are genuine, it’s sometimes hard to say for sure whether they are AI-generated, edited in some other way or created by an impersonator. But there’s no doubt that AI-generated deepfakes are becoming an increasingly common phenomenon on social media and elsewhere online.

This guide offers some practical tips on how to tell whether these kinds of clips are genuine, and how to spot deepfakes. There are few guaranteed ways to tell that video or audio was made using AI, but this is a good place to start if you suspect something you’ve seen isn’t genuine.

As this technology is fast improving, it may become increasingly hard to spot deepfakes—but we’ll aim to update this guide regularly with the best ways to identify them.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

But first, the basics—what is a deepfake?

At Full Fact, when we talk about deepfakes, we’re generally referring to video or audio that has been created using AI tools to at least semi-successfully mimic the face or voice of a public figure. Although the term ‘deepfake’ has been in use for at least five years, definitions still vary on whether it also includes AI-generated still images or not. We’ve written about AI-generated images of public figures including Julian Assange, the Pope, French president Emmanuel Macron and Princes Harry and William, all showing them doing things they haven’t actually done. We’ve written a separate guide on how to spot AI-generated images.

How are deepfakes made?

Broadly speaking, there are three types of video deepfakes of people.

There are ‘face-swaps’, like this one where actor Steve Buscemi’s face is projected onto fellow actor Jennifer Lawrence’s.

There are several apps available that allow you to ‘face-swap’ someone’s face onto a video of someone else, almost instantly. Some just need a single image of the person you want to make a deepfake of.

‘Lip-syncs’ take a genuine video of someone and use AI to adjust their mouth to make it look like they’re saying something else. These might be accompanied by audio that is AI-generated or created by an impersonator. We’ve checked multiple lip-sync videos in the past, including one of Bella Hadid which used a genuine clip of the model speaking at an event, and another of Mr Starmer that used footage from his 2023 New Year address.

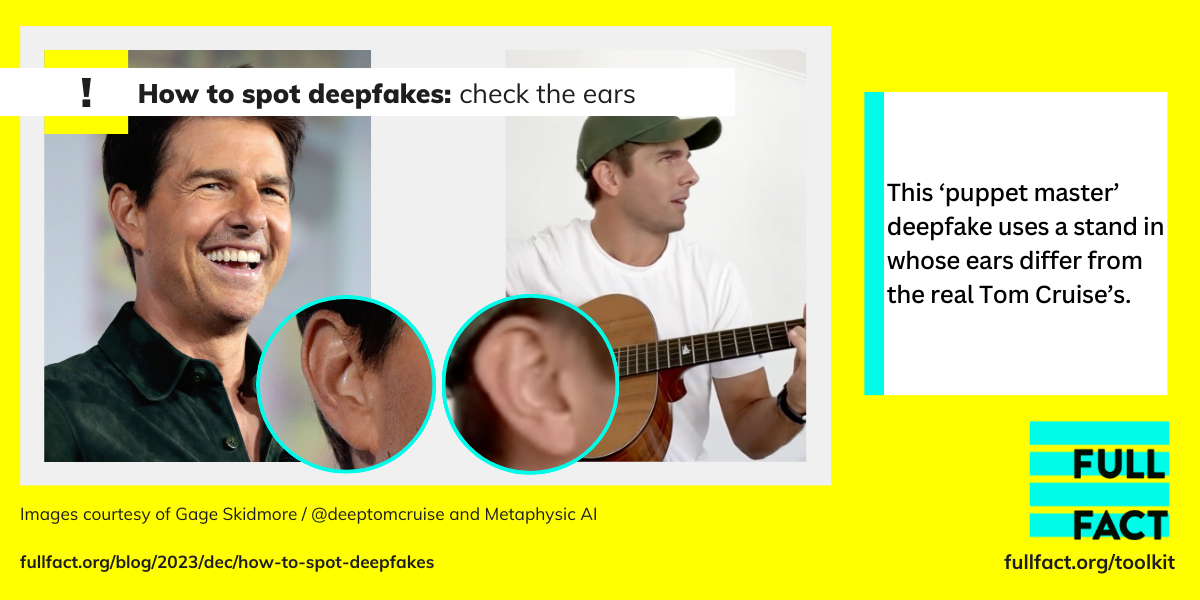

‘Puppet master’ deepfakes use AI to animate the entire head. While we haven’t fact checked any of these yet, the young Tom Cruise parody deepfake you may have seen is one of these.

There are apps that allow you to make all three types, as well as audio, including ElevenLabs, DeepFaceLab and more, by inputting very little data. Other methods require some coding and are a little more complicated, but there are many tutorials online guiding people on their use.

Deepfakes made in any of these ways can be convincing, especially if they’re tidied up using conventional editing software afterwards. Since they can now be made so easily, demanding relatively little time, effort or technical knowledge, it’s more likely than ever that you might encounter one that looks genuine.

If you’re interested in how AI images and videos are created technically, you can watch this in-depth video from Professor Hany Farid, an expert in digital forensics at the University of California, Berkeley in the US.

How to spot a deepfake video

If you suspect a video is a deepfake, take a look at it closely, on a screen bigger than your phone’s if possible. Try and find the highest quality version of it that you can, potentially by reverse image searching key moments in the video, which we explain how to do here.

Watch it carefully, and look out for the following giveaways:

1. Check the face shape (and the ears)

Does the outline of the person’s face match other images of the person? If not, this may be a clue that the footage is a ‘puppet master’ deepfake.

Chris Ume (the VFX and AI artist who created the parody Tom Cruise deepfake mentioned above) said in an interview on the YouTube channel Corridor Crew: “I think the shape of the face is always a giveaway... In a lot of cases, their measurements are not perfect.

“The best thing is just to hold a picture next to it, or a few pictures, and start comparing.”

He also commented that it’s difficult to fake ears, as they’re so specific to the person. His Tom Cruise deepfakes, which overlay the young actor’s face on a lookalike with a similar build and haircut, don’t attempt to fake Mr Cruise’s ears. Side-by-side comparisons show it isn’t him.

2. Can you find the original footage?

Looking at face shape won’t help you spot lip-sync or face-swap deepfakes though.

There are other ways to fact check content like this, such as finding the original source of the video by searching for keywords, or reverse image-searching screenshots. See more on how to do this in our guide on how to spot misleading videos.

3. Scrutinise expressions and mannerisms

Mr Ume also mentioned paying close attention to the look on the person’s face, saying: “In deepfakes you always lose expression”.

Does the celebrity have any particular mannerisms in the way they speak that are missing from the video?

Professor Farid calls these behavioural tells “soft biometrics”, and they can be used to differentiate someone from their deepfake or an impersonator. He uses the example of former US president Barack Obama’s head lift and slight frown as he said “Hi everybody” during his weekly addresses.

4. Are the eyes aligned?

Mr Ume pointed out that there are often issues with the alignment of people’s eyes in deepfakes.

“Only in still frames can you detect those [discrepancies],” he said. Pause the video a few times and check whether the eyes are looking in the same direction.

Like most of these tips, the presence or absence of this isn’t a guarantee either way—the deepfake might not include this error, or the real person may have a squint.

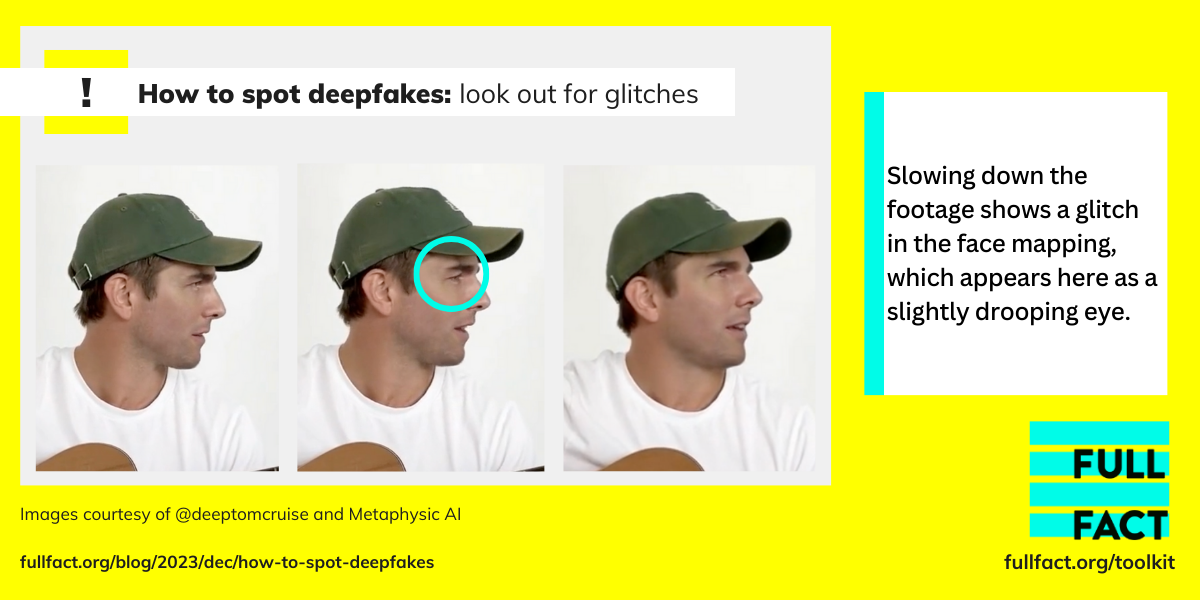

5. Look out for visual glitches

Deepfake videos are most convincing when the person is looking at the camera straight on. If a video has been made with AI, the technology may slip up when the person turns to the side or partially covers their face.

You may be able to spot such glitches if you slow down the footage (you can use a free app to help). This will make it easier to notice any points where the technology fails to perfectly match the AI-generated face over the real part of the video.

For example, this clip of the deepfake Tom Cruise shows a slight glitch when he turns back around to face the camera. It’s barely visible at normal speed, but if you go to YouTube’s settings and then change the playback speed to 0.25, you can see a computerised glitch in his eye.

6. Does the voice correctly sync with the video?

If you want to get a little more technical, you can start thinking about visemes, which are the broad positions of your mouth when you make different letter sounds.

According to Professor Farid in his video lecture on deepfakes: “There’s a certain shape that your mouth makes when you make certain sounds. And we hypothesised after looking a lot at some of the very good lip-sync deepfakes… that sometimes these phoneys’ viseme-matching aren’t quite right.”

He showed slowed-down clips of both real and deepfake versions of former US president Donald Trump making the “m” part of the word “I’m”. The deepfake Mr Trump’s mouth doesn’t fully close, which Professor Farid pointed out is impossible unless you’re a ventriloquist.

Professor Farid said in about a third of cases he’s looked at there’s a mismatch between an M, B or P sound and the lip-sync deepfake where the viseme isn’t consistent with one of those common sounds.

Audio clues

This year, we’ve written about two audio clips purporting to be of politicians which may have been made with AI. It’s very hard, even for professional audio experts, to tell whether audio is real or not—and if it’s not real, how exactly it was faked.

Audio-only deepfakes give you fewer potential AI slip ups to look out for. But there are still things to be wary of if you suspect an audio clip might be made with AI.

1. What are they saying?

Think about what the person in the clip is actually saying, and how they say it. In a recently debunked audio clip of Sir Keir Starmer supposedly endorsing an investment scheme, one of the giveaways that it was fake was that ‘Mr Starmer’ kept saying things like “pounds 35,000” instead of £35,000.

Are there any other discrepancies with how they phrase things that you might not expect?

Mike Russell, founder of the audio production company Music Radio Creative and a certified audio professional with more than 25 years of experience, told Full Fact to look out for issues with pronunciation or accent.

He said: “Sometimes AI will say words in an inconsistent style—for example, it will say "path" with a northern accent when the speaker [is] speaking in a southern accent.”

2. The sound of the voice itself

In a lip-sync deepfake of Kim Kardashian made by an art group, it’s clear if you compare it with the real version that the deepfake’s audio sounds like it may be an impersonator.

If you see a clip on your phone without sound and it has subtitles, make sure you actually listen to the audio to see if it’s convincing.

Mr Russell warns you should listen out for any digital glitches which may include “robotic sounds” in parts of the speech. Are there unnatural pauses? Do the pitch and speed of the voice sound right?

3. Background noise

Mr Russell also advises paying attention to background noise.

“Is it consistent or does anything change in relation to the background sounds during the speech?” he said.

Be suspicious

As AI technology advances, the above tips for spotting deepfakes will likely date fast. We’ll update this guide to cover new developments as they emerge.

Professor Farid told Full Fact that even using his advanced forensics tools, “we often will find artefacts in AI-generated content that months later are corrected by an updated AI model”.

He added: “We all have to learn how to be better consumers of online information and learn how to resist the temptation to amplify false information. This includes slowing down, checking our online rage, getting out of our filter bubbles, fact checking before sharing, and more generally remembering that we can disagree without demonising or hating.”

As we say in our other guides to spotting misleading content, always consider whether the scenario seems realistic. If not, do any of the above clues apply? These don’t prove something is definitely a deepfake, but you may want to hold off sharing something if alarm bells are ringing.

And having a Google of relevant keywords is always a good way to check if something’s real. Is what you’re seeing being reported by any trustworthy news sources? A quick online search would show you that BBC presenters hadn’t actually endorsed an investment project, despite what a deepfake video showed.

A word on tools

There are many tools that claim to be able to tell you, some with a specific percentage of confidence, whether an image or video was generated using AI. However, at the time of writing, Full Fact doesn’t quote these tools in our articles because we find they just don’t work consistently.

Professor Farid said the same in an interview [this link contains graphic images] with tech publication 404 media regarding an apparently real image that surfaced during the Israel-Gaza conflict purporting to show the burnt body of a baby. Some online had put the image into a free AI checker tool, which concluded—apparently wrongly—that the image was made with AI.

Professor Farid told 404 media that the way these “black box” automated tools work is “not very explainable”.

“You need to reason about the image in its entirety. When you look at these things, there need to be a series of tests. You can’t just push a button to get an answer. That’s not how it works.”

In his podcast about the probable deepfake audio of Mr Starmer swearing, Mr Russell also noted that tools alone can’t confirm whether something is a deepfake—with some of the tests he ran suggesting that the audio was actually real.

He said: “I think we don’t have advanced enough tools to tell us if something that’s generated is fake or not.

“If you can upload something that’s cleanly generated by an AI voice cloner or deepfake voice generator and it will say ‘yes, 98% sure we made this’, and then you can add a bit of background noise and some EQ shaping [advanced audio editing] and it’s like ‘98% sure that’s human’, then we definitely stand in a world where stuff can be created and no one can be any the wiser.”

Other harmful deepfakes

Some of the deepfakes we’ve written about may have been created simply to fool people, or to change people’s perception of public figures, including politicians. Others appear to have been made to make money, by falsely claiming a business has been endorsed by a celebrity or public figure.

We’ve also seen reports of scammers creating deepfakes of someone’s friends or family and using those to request money, relying on the victim’s fear about their loved one’s alleged situation to make them overlook inconsistencies with the deepfake itself. Other scammers target businesses, banks or trick people into transferring money to their colleagues.

Particularly concerning is the trend of deepfake pornography being made of women and girls, both famous and otherwise, without their consent.

Helen Mort, who made a documentary for the Guardian about her experience finding out her likeness was being used in such deepfakes, wrote: “Some of them were like grotesque Photoshop jobs—obvious fakes. Others were more plausible, realistic images depicting violent sex, photos that could have been genuine. All of them were profoundly unsettling.”

If you can’t tell if a video is a deepfake

If you do come across any suspected deepfakes online, please do send them our way for fact checking. You can get in touch via our website or tag us on X (formerly Twitter).

And if you’d like more tips on how to check other kinds of misinformation, check out the Full Fact toolkit.