Asylum seekers, the UK and Europe

Migrants and asylum seekers have been crossing the Mediterranean Sea in record numbers since the summer of 2015, and many have died trying. This mass movement of people has been a big issue across the world.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Over one million arrivals last year

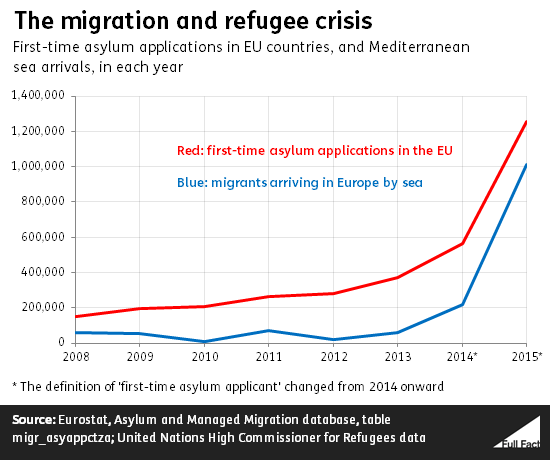

Last year, the UN refugee agency recorded just over one million people arriving in Europe over the Mediterranean. Another 328,000 have come so far in 2016. The International Organisation for Migration has almost identical figures.

That compares to 216,000 in 2014 and fewer than 100,000 in each of the years before that.

An estimated 3,800 people died or went missing on the Mediterranean in 2015.

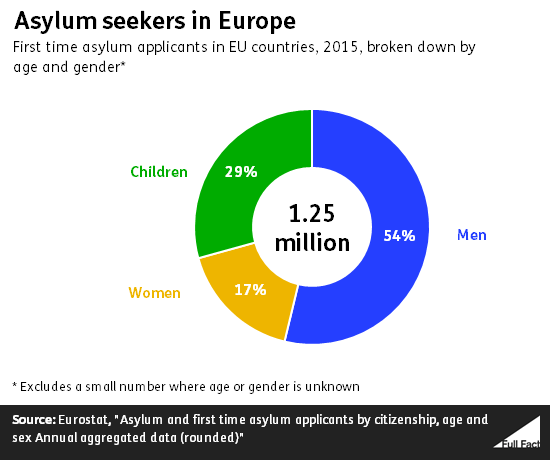

The majority of asylum seekers were men

More men than women and children applied for asylum for the first time in 2015. Overall, almost three quarters of first-time asylum seekers of all ages were male.

There were 88,000 asylum seekers “considered to be unaccompanied minors”—in other words, children travelling without their family.

This is a similar breakdown to those recorded arriving on European shores over the course of 2015 and 2016.

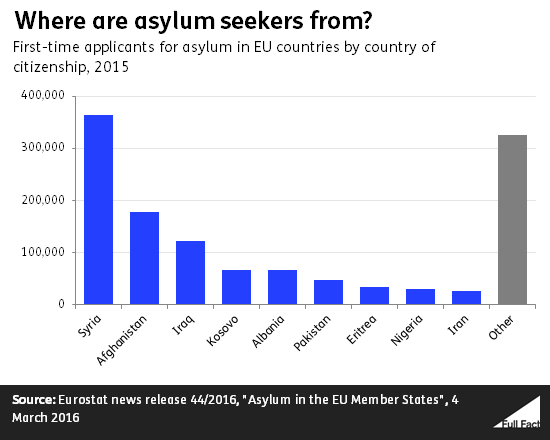

Around three in every 10 people applying for asylum for the first time last year was Syrian. Over half were from one of Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq.

People from those countries are likely to be successful in an EU asylum application, whereas people from countries like Kosovo or Albania are very unlikely to be accepted.

Where are asylum seekers ending up?

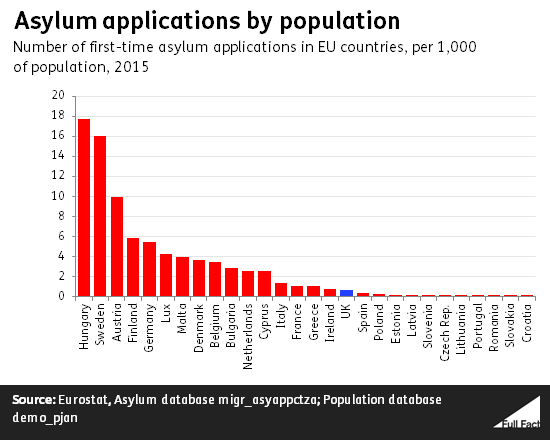

Germany, in a lot of cases. It accounted for 440,000 of the EU’s 1.25 million new asylum applicants last year from outside the EU. The UK recorded around 40,000 applications, the ninth highest in the EU.

Hungary recorded the second largest number of new asylum applications (170,000), just ahead of Sweden (160,000). That puts those two countries top of the list for asylum applications per head of population in 2015.

But this should be taken with a pinch of salt: a huge number of the applications in Hungary are deemed to be ‘withdrawn’, perhaps as asylum seekers move on into northern Europe. Over 100,000 asylum seekers who’d begun an asylum application in Hungary withdrew it in 2015, far more than in any other country.

So it’s worth looking at the number of asylum applications actually granted in various countries last year. Germany is way out ahead with 148,000, followed by Sweden, Italy, France and the UK (18,000). Hungary accepted 545.

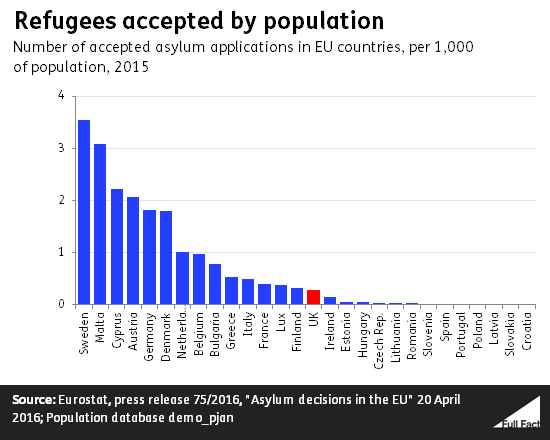

In terms of refugees per head of population, Sweden accepted the most last year.

There are also statistics on the ‘acceptance rate’, or percentage of decisions on asylum that led to the applicant being allowed to stay. In those terms, Bulgaria was the most accepting last year, and Latvia the least.

Countries outside Europe are taking in far more refugees from the conflict in Syria. The UN refugee agency reports “slightly more than 10% of those who have fled the conflict seeking safety in Europe”.

At time of writing, there are 2.7 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, over 1 million in Lebanon and 660,000 in Jordan.

How does that compare to the UK?

The UK doesn’t accept asylum applications from abroad, and within the EU people are supposed to apply to the first safe country they arrive in.

That in combination with our physical distance from Africa and the Middle East means comparatively few asylum seekers reach the UK.

In 2015, the UK accepted roughly 20,000 refugees. That’s counting people accepted through the normal, in-country asylum process, as well as those brought over from other countries under ‘resettlement’ schemes.

Asylum seekers make up around 4% of immigrants to the UK. People accepted as refugees make up around 20% of those given permission to settle here.

Not all arrivals are necessarily refugees, but asylum applications have risen too

It’s hard to know how many migrants are asylum seekers, and of those how many will ultimately be granted refugee status—which is why the choice of term in reporting on this issue has been controversial.

It’s been argued that most of those crossing the Mediterranean are coming here for a better life rather than fleeing persecution.

Many are coming to Europe from places they have already been granted asylum, such as Turkey and Jordan, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

UN profiles of arrivals on Greek islands in early 2016 provide some evidence of this. They show that between one in six and one in three Syrians, and up to 45% of Afghans, lived in another country for at least six months before crossing the Mediterranean (including Afghans born and raised in Iran). We’re not aware of any large-scale studies.

We know there has been a big rise in the numbers applying for asylum in EU countries. There were 1.26 million new people applying for asylum in 2015, well over double the 560,000 applicants the previous year.

Those figures can’t be compared directly to the UN records of arrivals, as there’s a time lag between someone arriving in, say, Greece and applying for asylum in a country like Germany. They still give a fair indication that most of those arriving are at least applying for asylum.

Refugees’ right to move around the EU

It’s sometimes claimed that other EU countries granting people asylum will give them the right to come to the UK, because of EU rules on free movement of people.

People granted refugee status in an EU country can get the right to move to most other EU countries if they've been living here "legally and continuously" for five years. But the UK is an exception: we've chosen not to be covered by this law.

So refugees in an EU country like Germany would need to become citizens of that country in order to benefit from free movement rights and come here.

The length of time that takes varies across the EU. Refugees are entitled to citizenship after eight years in Germany, for instance, whereas in other countries citizenship is at the discretion of the government. It can be granted after five years in Italy and four years in Sweden, according to the European Union Democracy Observatory.