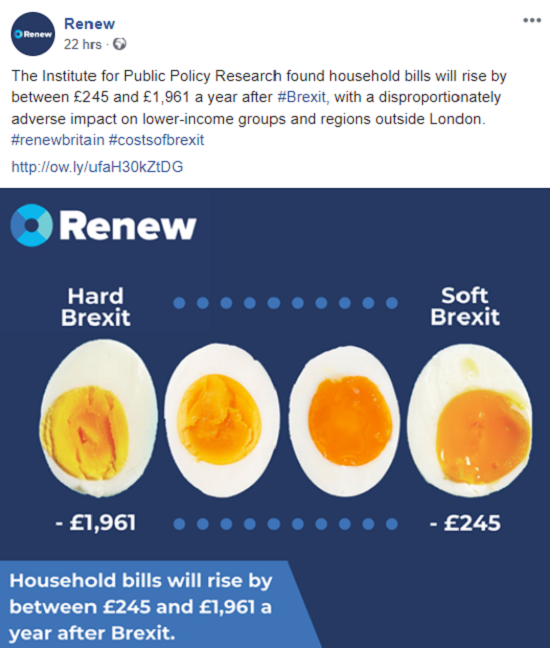

“The Institute for Public Policy Research found household bills will rise by between £245 and £1,961 a year after #Brexit, with a disproportionately adverse impact on lower-income groups and regions outside London.”

Renew Party, 18 July 2018.

This is a case of a series of crossed wires. The estimated household cost increase following a “hard Brexit” was £961, not £1,961, and was calculated by consultancy Oliver Wyman, not think tank The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).

Oliver Wyman estimated that a “hard Brexit” scenario with World Trade Organisation tariffs would add 4%, or £961, onto average annual household costs. The Brexit scenario with the lowest impact on bills (a “moderate amount of red tape” scenario”) would increase annual household costs by 1% or £245, as the graphic correctly states.

The £1,961 figure originates from a typo in an article by the Guardian which has since been corrected.

That article discussed both the Oliver Wyman report and a separate report by the IPPR looking at the possible effects of Brexit on income inequality, which may be the source of confusion.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The claims about the impact on lower-income and non-Londoners are a bit confused

The claim that IPPR said Brexit will have a disproportionately adverse impact on lower-income groups and regions outside London isn’t quite right.

In fact the IPPR said that “price impacts have a broadly neutral effect on income inequality”, adding that “while Brexit is unlikely to worsen income inequality, all income groups – including the poorest - will face negative impacts.” They do however note that lower income households have “less of a ‘buffer’ to protect them from increased prices”.

The Oliver Wyman report said a “hard Brexit” scenario could increase costs for low-income households by 3% more than high income-households. They also said a different scenario, with increased labour costs, could flip that situation – with household costs for higher earners increasing by 4% more than for lower earners.

As for geographical inequality, the IPPR said the regional effects of Brexit on jobs are hard to determine with certainty but that “most studies suggest that in the long run it is areas outside London and the South East that are most likely to suffer from a downturn.”

With regards to household costs, it estimated that regions outside London would be most affected saying: “London is least affected because a greater proportion of households’ expenditure goes on housing costs, which are not expected to be significantly impacted by Brexit.”

Nevertheless it acknowledged dissenting views such as analysis from the London School of Economics which, on jobs, said that service sectors would be more negatively affected by Brexit than other sectors, and that because London and the South East have the highest concentration of services industries, those regions will be hit the hardest by Brexit.

The IPPR concluded by saying: “Our analysis suggests that claims that Brexit will benefit the worst off or entrench inequalities further as too simplistic. The available research suggests that exiting the EU – in particular a hard Brexit – will have a negative GVA and price impact across different income groups, regions, genders and ethnicities, but it will not necessarily increase inequalities.”