EU immigration and NHS staff

EU immigrants make up about 5% of English NHS staff and about 5% of the English population, according to the best available data. Across the UK, EU immigrants make up 10% of registered doctors and 4% of registered nurses. Immigrants from outside the EU make up larger proportions. Restrictions on non-EU immigrants have affected NHS recruitment, suggesting that the same could happen if there were limits on EU immigration. However, these restrictions did not trigger a process of existing healthcare workers fleeing the UK

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

What proportion of the NHS’s staff come from the European Union?

The nationality of NHS staff

55,000 out of the 1.2 million staff in the English NHS are citizens of other EU countries, according to the English Health Service’s Electronic Staff Record. This includes doctors; nurses; other professionals like paramedics and pharmacists; support workers providing care; and administrative staff.

Assuming that the staff who were not asked or did not fill out this field had a similar mix of nationalities to those who did, this implies about 5% of NHS trust staff are citizens of another EU country – compared to around 5% of the population of England.

10% of doctors and 4% of nurses are from elsewhere in the EU

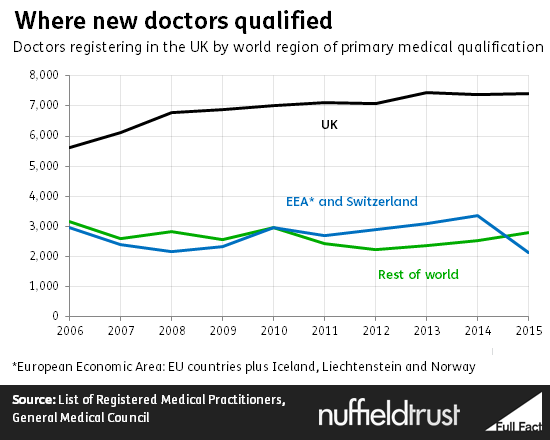

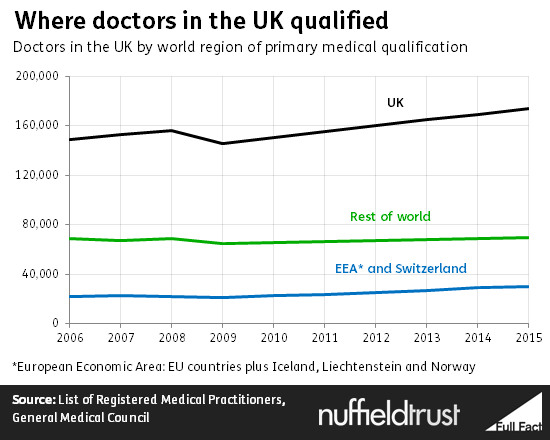

We can get a fuller picture in the case of doctors and nurses by looking at the records their regulators keep of where each person registered in the UK carried out their original training. This should include EU migrants who been here several years and obtained British citizenship, and allows us to look across all four home nations.

Doctors from the European Economic Area (the EU plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) have long made up a significant proportion of the UK’s medical workforce. Academics have singled out the UK as one of the developed countries that relies most on importing doctors trained abroad.

Most come from outside Europe, but more than one in ten of those registered to practise as a doctor (a group which may include some people who have retired or are in other lines of work) is an EU immigrant.

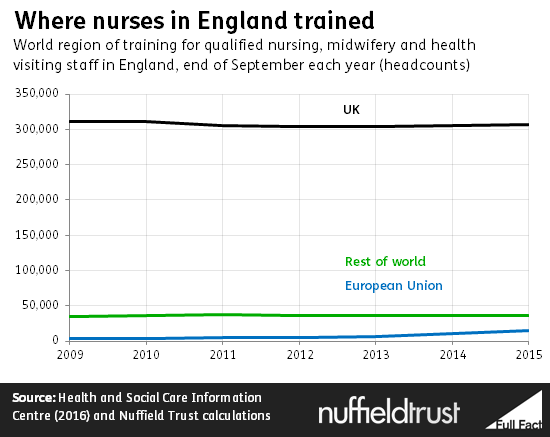

The proportion of registered nurses and midwives from the EU is lower, at slightly above 4%. However, this represents a sharp expansion from even a few years ago. EU immigrant nursing numbers have risen at a time when the numbers of British-trained nurses has actually fallen.

The measure of where somebody is trained or professionally qualified is not easy to duplicate across the whole population. But we do know that 4.7% of the general UK population were born in other EU countries.

What can we conclude?

Although data is far from complete, there are a few points which seem clear about the number of EU migrants working in the NHS.

Firstly, EU migrants make up a significant proportion of NHS staff – over 10% in the case of doctors – but not as large a proportion as non-EU migrants.

Secondly, EU migrants are slightly more likely than the population overall to be NHS staff generally. They are disproportionately likely to be doctors – but not to be nurses.

Lastly, in nursing and midwifery EU immigrants make up a small proportion, but their numbers have been increasing at a historically rapid rate in in recent years as the number of nurses trained in Britain has dropped. Without this, overall nursing numbers would have fallen rather than remaining more or less steady.

What could be the impact of Brexit, and the changes accompanying it, on the future Health Service workforce?

Leaving the EU would allow the UK to restrict the flow of immigrants from Europe. Campaigners in favour of Britain remaining in the EU have argued that this could cause an NHS staffing crisis.

They have suggested this could be caused directly through new restrictions preventing EU-born NHS staff from working in Britain, or indirectly because EU-born staff will leave the UK pre-emptively due to the “uncertainty” created when migration restriction becomes possible.

How can we inform our estimate of the effect a post-Brexit immigration tightening would have on the NHS?

There is no exact precedent to look at to judge these claims, as they depend on hypothetical decisions and perceptions after a British exit.

However, one imprecise precedent is the substantial tightening of rules for non-EU immigrants around 2010. This saw the elimination of general visas for highly skilled workers from outside the EU who did not have a job offer in the UK.

At the same time, migration for most categories of worker who did hold a job offer was capped. This followed changes made by the previous Labour government in 2008 and 2009 introducing a points-based system for these skilled visa categories.

There are good reasons to see this as a relevant example. If EU immigrants were simply treated in the same way as non-EU immigrants after exit from the union, these would be the exact rules applied. Even if some other package of restrictions was used, these rules reflect themes which have been cited by many proponents of leaving the European Union: reductions or caps in numbers, an emphasis on only allowing immigrants with especially economically valuable skills, and the use of a points-based system.

Did the changes around 2010 have a real impact on NHS recruitment over the following years?

Over the years following 2010, it does appear that the package of restrictions had a subtle but clear impact on NHS recruitment.

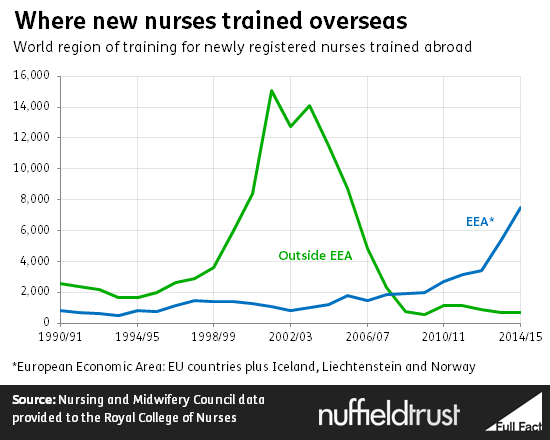

The Royal College of Nursing makes the case that there have been two periods of nursing shortage in the Health Service’s recent history: one immediately after the year 2000, and one in the last few years. Although comparable data on vacancy rates does not exist, trends in overall nursing migration seem to support this.

During the first shortage, migration from outside the European Economic Area filled much of the gap, rising to close to 15,000 nurses each year. The current shortage, however, has seen no noticeable increase in non-EEA nursing migration, which has remained below 1,000. Instead, migration within the EEA has expanded somewhat to around 7,000 each year to keep up with the Health Service’s need for nursing staff.

The economic situation in Southern European countries accounts for the rise in European migration. However, academics looking at the change have concluded that the key factor in the lack of non-EU clinical migration in this shortage period was the change in policies.

NHS Employers, representing the trusts where nurses work, has pointed to the need to obtain sponsorship certificates and the presence of an overall cap as obstacles to recruitment from outside the EEA. This suggests that it has been politically feasible to introduce laws which meaningfully restrict NHS migrant staff, and that the effect of this has been substantial.

Did staff leave pre-emptively due to concern at the direction of policy?

There was no evidence of a collapse in the numbers of non-EU nurses suggesting a general flight motivated by uncertainty. These remained steady at around 37,000.

The rate of non-EU doctors registering in the UK slowed slightly after 2010, as shown below. However, there is again no sign of pre-emptive flight. The total number of doctors trained outside the EU has still been rising by several hundred each year.